My Trip to The Filson

Tentative Relations: Secession and War in the Ohio River Valley, 1859-1862

By: Timothy Jenness

University of Tennessee, Filson Fellow

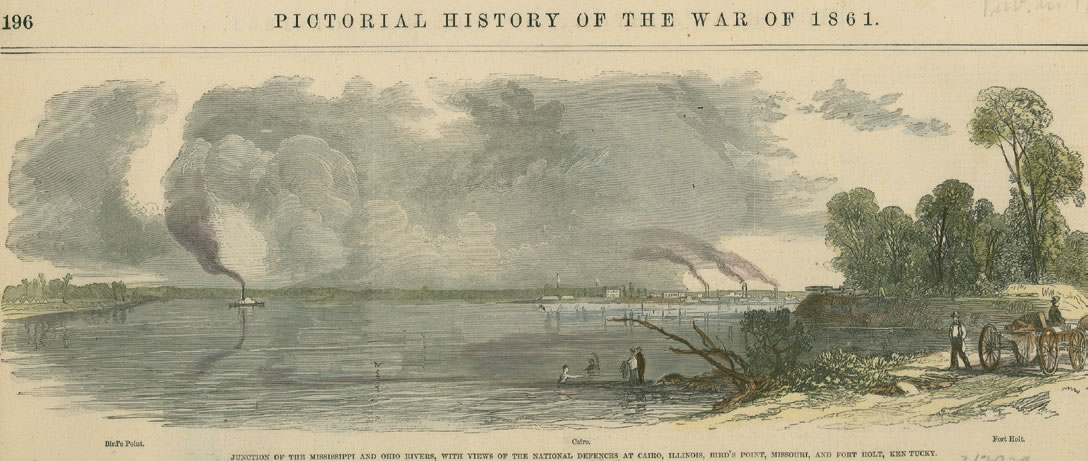

Mountains, rivers, lakes and swamps dominate the American landscape. These geographical features often serve as hurdles to be overcome or lines of demarcation across which people hesitate to venture. In American history, the mighty Ohio River sometimes played such a role. Yet, during the colonial era and into the 19th century, the Ohio carried goods and people downstream to the Mississippi River and New Orleans. With the arrival of steam power, the river became a two-way thoroughfare that retained its importance even after the railroad put a significant dent in its commercial traffic. Antebellum Americans recognized that the Ohio River served as the proverbial line in the sand between the free North and the slave-holding South. That fact was not lost on people who lived in the Ohio Valley towns adjacent to the river or whose livelihood depended on it.

Mountains, rivers, lakes and swamps dominate the American landscape. These geographical features often serve as hurdles to be overcome or lines of demarcation across which people hesitate to venture. In American history, the mighty Ohio River sometimes played such a role. Yet, during the colonial era and into the 19th century, the Ohio carried goods and people downstream to the Mississippi River and New Orleans. With the arrival of steam power, the river became a two-way thoroughfare that retained its importance even after the railroad put a significant dent in its commercial traffic. Antebellum Americans recognized that the Ohio River served as the proverbial line in the sand between the free North and the slave-holding South. That fact was not lost on people who lived in the Ohio Valley towns adjacent to the river or whose livelihood depended on it.

My dissertation, “Tentative Relations: Secession and War in the Ohio River Valley, 1859-1862,” explores the myriad ways in which people living in the river counties between Louisville and Cincinnati responded to the secession crisis. In looking at communities on both sides of the river, I seek to demonstrate that although the Ohio River may have separated people geographically, the region consisted of intricate relationships that crossed the river and, ultimately, influenced peoples’ reaction to secession and the outbreak of hostilities. In some ways, the border state mentality articulated by many Kentuckians living along the river resonated with Hoosiers and Buckeyes living directly across the water on the Ohio’s northern bank. People on both sides of the river shared a warm relationship before Abraham Lincoln’s election. That bond grew strained, however, as the secession crisis disintegrated into civil war. Rarely far from peoples’ minds was the realization that secession and war affected their daily lives even if Confederate troops were hundreds of miles away.

The Filson Historical Society holds an extensive collection of primary documents that shed considerable light on the role of Kentuckians during the Civil War. The Bush-Beauchamp Papers, John F. Jefferson Papers, Holyoke Family Papers and the Alfred Pirtle Journal, for instance, are but a few of the fine collections whose content enrich historians’ understanding of the complicated nature of regional identity in the central Ohio Valley.

The Filson Historical Society holds an extensive collection of primary documents that shed considerable light on the role of Kentuckians during the Civil War. The Bush-Beauchamp Papers, John F. Jefferson Papers, Holyoke Family Papers and the Alfred Pirtle Journal, for instance, are but a few of the fine collections whose content enrich historians’ understanding of the complicated nature of regional identity in the central Ohio Valley.

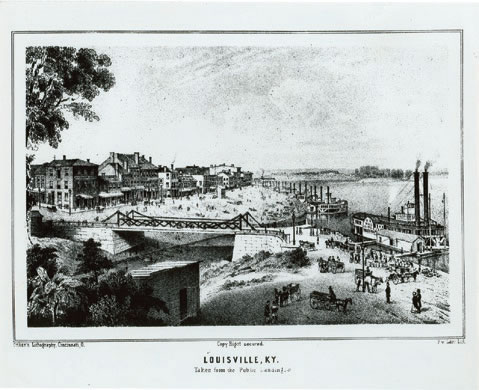

Of immediate concern to the new Lincoln Administration were the war supplies heading south to the Confederacy via the Ohio River and Louisville and Nashville Railroad. In May 1861, Louisville grocer John Jefferson commented on the Federal effort to stop such trade. “Orders were received from the US Government to-day,” he wrote, “to blockade the Railroads and River. The news caused great excitement here. Bacon . . . fell in price immediately.” Louisvillians felt the ramifications of such a decision. Apparently Jefferson quit buying bacon because of his fear that he would not be able to sell it. By June when the “blockade” of the L&N Railroad took effect, patrons of Jefferson’s store found it increasingly difficult to pay the money they owed the merchant.

Louisville residents of different sympathies expressed dismay that Federal authorities “blockaded” portions of the Ohio Valley because supplies destined for the Confederacy passed through the city. One man grumbled to Samuel Crockett, “You have doubtless heard of the blockade of Louisville, New Albany and Jeffersonville. We are hemmed in by water certain, no boats of any consequence are permitted leave without being thoroughly overhaul[ed].” Federal authorities examined ships coming from Indiana and Cincinnati, he said, “in search of contraband of war and provisions destined to the South.” What angered the man even further was the fact that the increased federal presence hindered local trade.  Poor farmers in Indiana were not able to bring their produce to market, he noted. “The citizens of Indiana are not allowed to bring even so much as one dozen eggs to our market,” he complained, “for fear they will be aiding and abetting the South, in their work of dishonoring the Union.” Just weeks after the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter and prior to the first major battle at Bull Run in July, denizens of the central Ohio Valley found their daily lives circumscribed by war.

Poor farmers in Indiana were not able to bring their produce to market, he noted. “The citizens of Indiana are not allowed to bring even so much as one dozen eggs to our market,” he complained, “for fear they will be aiding and abetting the South, in their work of dishonoring the Union.” Just weeks after the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter and prior to the first major battle at Bull Run in July, denizens of the central Ohio Valley found their daily lives circumscribed by war.

Although sometimes strained, the relationship between residents of Kentucky, Indiana and Ohio’s river counties endured. Shortly after the Confederate invasion of Kentucky in Sept. 1861, Kentuckian Maria Holyoke informed her sister in New York that “the Union feeling” dominated Louisville. If that were not enough, she announced, “we shall have aid from Ohio and Illinois” to supplement the “thousand or more Indiana troops” pouring across the Ohio River. For this woman, the excitement was almost too much. She asked her sister to read the paper clippings she included in her letter because, she admitted, “I am so excited I cannot make things clear.”

The staff at The Filson Historical  Society offers a cooperative and collaborative environment in which to do research. I am indebted to the Filson’s Director Mark Wetherington, A. Glenn Crothers and James Holmberg and his staff for providing assistance and support during my stay. Their collegiality and knowledge of the collections and region are an invaluable part of the many services they provide to researchers interested in Kentucky and Ohio Valley history.

Society offers a cooperative and collaborative environment in which to do research. I am indebted to the Filson’s Director Mark Wetherington, A. Glenn Crothers and James Holmberg and his staff for providing assistance and support during my stay. Their collegiality and knowledge of the collections and region are an invaluable part of the many services they provide to researchers interested in Kentucky and Ohio Valley history.

About |

Past Issues of the Newsmagazine

The Filson Historical Society

1310 South Third Street - Louisville, KY 40208

Phone: (502) 635-5083 Fax: (502) 635-5086

Hours

The Ferguson Mansion and Office

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday and Sunday closed

Library and Special Collections

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

First Saturday of every month: 9 am. - 4 pm.