Colonel William Stewart Hawkins, CSA: Prisoner and Poet of Camp Chase, Ohio

By Noah Huffman

Special Collections Assistant

About |

“Pardon me if the expressions of my gratitude for your sisterly kindness and sympathy have

been too warm. . .” — Colonel William S. Hawkins, 11th Tenn. Cavalry

“Pardon me if the expressions of my gratitude for your sisterly kindness and sympathy have

been too warm. . .” — Colonel William S. Hawkins, 11th Tenn. Cavalry

Confederate prisoner Colonel William S. Hawkins wrote these lines to Lucy G. Tucker of Louisville in an 1864 letter now housed in The Filson’s recently cataloged Tucker family papers. While the Tucker collection contains several other items pertaining to this prominent 19th century family of Louisville, such as correspondence, land surveys, church covenants, and wills, it is the six letters and three original poems of Col. William Hawkins that make this small collection particularly interesting and revealing.

Born in Madison County, Alabama in 1837, William Hawkins expressed

an early interest in literature and poetry. He studied both at the

University of Nashville and later at Bethany College of Virginia, where he

received his degree in 1858. Hawkins then studied law under Tennessee

Governor Neill S. Brown and built a reputation as an outspoken advocate

of secession. Shortly after war broke out in 1861, Hawkins left his young

wife and child and volunteered for a Tennessee cavalry unit. After

distinguished service at the Battle of Shiloh, he was promoted to the

11th Tennessee Battalion, where he commanded Joseph Wheeler’s

Mounted Scouts. In January of 1864, however, Hawkins military

career ended abruptly when he was captured by Union forces and taken

to a  Louisville hospital as a prisoner

of war.1 It was in Louisville that

Hawkins, 27, first met the 42-yearold Lucy G. Tucker, whom he later

described as “my special providence in this prolonged and dreary life as a

captive.”

Louisville hospital as a prisoner

of war.1 It was in Louisville that

Hawkins, 27, first met the 42-yearold Lucy G. Tucker, whom he later

described as “my special providence in this prolonged and dreary life as a

captive.”

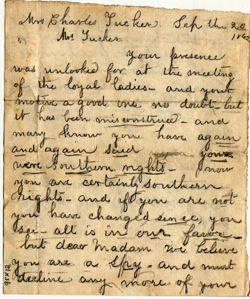

Twenty years earlier in 1843, Lucy had married Charles S. Tucker

of Louisville, a prominent financial broker in the city. Together the couple

took up residence at “Hayfield,” the family estate just east of town, where

they raised their four children and lived a life typical of the city’s elite.

When war erupted, the Tuckers cast their lot with the Confederacy, and as

a result, Lucy found herself in the same predicament that similar Kentuckians

faced. In September of 1862 she wrote: “I remain loyal to our state,

but nevertheless feel a strong sympathy for our southern friends.” During the

first few years of the war, she attended meetings of the Humane Ladies

of  Louisville, an organization that

prepared bandages and other supplies for wounded Union soldiers. But when

rumor spread through the organization that Lucy supported “southern rights,”

a fellow Humane Lady wrote to her declaring, “We believe you are a spy,

and must decline any more of your assistance in preparing comforts for

the union party.” Angered by the accusation, Lucy wrote to the local

doctor who had provided instruction to the group and suggested that even

though her loyalties lay with the South, she had “quite as much claim

to the name of ‘humane’ ladies” as anyone else in the organization. By

Louisville, an organization that

prepared bandages and other supplies for wounded Union soldiers. But when

rumor spread through the organization that Lucy supported “southern rights,”

a fellow Humane Lady wrote to her declaring, “We believe you are a spy,

and must decline any more of your assistance in preparing comforts for

the union party.” Angered by the accusation, Lucy wrote to the local

doctor who had provided instruction to the group and suggested that even

though her loyalties lay with the South, she had “quite as much claim

to the name of ‘humane’ ladies” as anyone else in the organization. By

1864, though, Lucy was no longer attending meetings of the Humane

Ladies. Instead, she was attending to sick and wounded Confederate soldiers

who passed through Louisville on their way to northern prison camps in Ohio

and Illinois. In January of 1864, one of these patients was Colonel William

Hawkins.

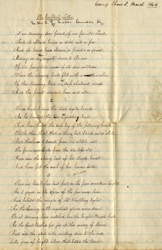

In the few weeks after his capture and before his transfer to Camp Chase

near Columbus, Ohio, Hawkins convalesced in a Louisville hospital

“suffering considerably from an affliction of the throat.” Sometime

during his short stay in Louisville, Lucy Tucker  impressed Hawkins with

her “gentle kindness” and her generous assistance. He would never forget it,

and in the following months he sent Lucy a series of letters

and poems from Camp Chase expressing his profound appreciation for her friendship amidst

the privations of prison life. In February 1864, Hawkins wrote about

a recent dream he had: “I thought I heard the light fall of a woman’s step,

the gentle rustling of her robe, and fancied I was in Louisville at some

friend’s house and that you had come to see me.” Accompanying the letter,

Hawkins included an original poem written for Tucker entitled “Behind

the Bars,” in which he captured the anguish of his captivity and his

longing for a woman’s companionship. The poem began: “Though I rest within a

prison / and long miles between us be, / yet through bonds and weary distance,

Sweet, / my soul goes out to thee.”

impressed Hawkins with

her “gentle kindness” and her generous assistance. He would never forget it,

and in the following months he sent Lucy a series of letters

and poems from Camp Chase expressing his profound appreciation for her friendship amidst

the privations of prison life. In February 1864, Hawkins wrote about

a recent dream he had: “I thought I heard the light fall of a woman’s step,

the gentle rustling of her robe, and fancied I was in Louisville at some

friend’s house and that you had come to see me.” Accompanying the letter,

Hawkins included an original poem written for Tucker entitled “Behind

the Bars,” in which he captured the anguish of his captivity and his

longing for a woman’s companionship. The poem began: “Though I rest within a

prison / and long miles between us be, / yet through bonds and weary distance,

Sweet, / my soul goes out to thee.”

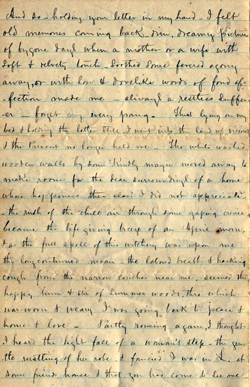

Both flattered and taken aback by the intimacy of

Hawkins’ letters and poems, Lucy felt obligated to question the

colonel’s motives. In response, Hawkins defended the expressions of

his affection for Lucy and argued that he intended nothing but to

acknowledge her cherished friendship. However, he did concede

that perhaps the psychological toll of his imprisonment had compromised his

good judgment. Nevertheless, Hawkins  pleaded, “I

have no other liberty, give me at least a little in my letters.” As their

correspondence progressed, Hawkins’ letters and poetry became more

playful. “It is philosophy spiced with a little fun and set off with a few flowers

of poetry,” he explained.

pleaded, “I

have no other liberty, give me at least a little in my letters.” As their

correspondence progressed, Hawkins’ letters and poetry became more

playful. “It is philosophy spiced with a little fun and set off with a few flowers

of poetry,” he explained.

When not flattering Lucy in his letters, Hawkins insisted that he remained in high spirits during his captivity. Apologizing for his sad expression in a photo he sent to Tucker, Hawkins wrote: “Now ordinarily I have neither a sleepy or demure look. I never have the blues, am always cheerful, and often hilarious.” In a March 1864 letter, Hawkins bragged that the other officers at Camp Chase had elected him Chief Executive of their provisional prison government. “The race was exciting,” he declared “some of the planks of my platform were ‘Equal Rights and Equal Rations,’ ‘Death to Detectives!’ and ‘a Speedy Exchange.” He also noted that he was responsible for organizing a Lyceum in the camp, “which holds its sessions twice a week for debates, essays, lectures, etc.” Overall, Hawkins sought to give Tucker the impression that, although he was a prisoner of war, he was not defeated. “I mention these things to show you that we are not stagnating,” he wrote. “We wreathe our manacles with garlands.”

Despite such attempts to demonstrate his self-sufficiency, the

fact remained that like the other 8,000 prisoners at Camp Chase, Hawkins

depended largely on the kindness of

outsiders for his very survival. As

other letters in the collection indicate, many Confederate prisoners in

the north were unprepared for the harsh winters they endured at places

like Camp Chase and Rock Island, Illinois. “The very climate is down

on us poor Secesh,” Hawkins wrote in January 1865. For clothing and

other rations, Confederate prisoners in the north often relied on southern

sympathizers in the border states—people like Lucy and Charles

Tucker. In an April 1864 letter, Hawkins wrote to Lucy: “I

am compelled for the time being to be under obligations to some one. I

desire therefore two sets light underwear . . . collars . . . and

an overcoat.” Judging from Hawkins’ letters, it is likely that

Lucy provided these items. In exchange for her generous aid, Col. Hawkins gave

Lucy the only thing he could—his poetry and his charm. We may never

know to what extent Hawkins really cared for Lucy Tucker, but through

his sentimental letters and poetry he ensured a ready supply of underwear

and other critical rations to get him through the long Ohio winter. Thus,

as Hawkins’ example illustrates, many Civil War prisoners often

survived on their charm and cunning rather than their bravery and brute strength.

outsiders for his very survival. As

other letters in the collection indicate, many Confederate prisoners in

the north were unprepared for the harsh winters they endured at places

like Camp Chase and Rock Island, Illinois. “The very climate is down

on us poor Secesh,” Hawkins wrote in January 1865. For clothing and

other rations, Confederate prisoners in the north often relied on southern

sympathizers in the border states—people like Lucy and Charles

Tucker. In an April 1864 letter, Hawkins wrote to Lucy: “I

am compelled for the time being to be under obligations to some one. I

desire therefore two sets light underwear . . . collars . . . and

an overcoat.” Judging from Hawkins’ letters, it is likely that

Lucy provided these items. In exchange for her generous aid, Col. Hawkins gave

Lucy the only thing he could—his poetry and his charm. We may never

know to what extent Hawkins really cared for Lucy Tucker, but through

his sentimental letters and poetry he ensured a ready supply of underwear

and other critical rations to get him through the long Ohio winter. Thus,

as Hawkins’ example illustrates, many Civil War prisoners often

survived on their charm and cunning rather than their bravery and brute strength.

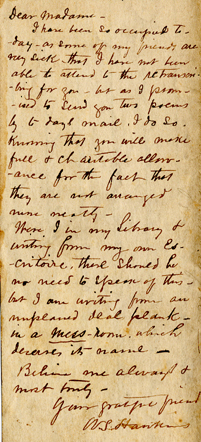

In a December 1864 letter, a jubilant Hawkins informed Lucy of his

parole and his appointment to serve as an official Confederate

Agent at the prison. However, in his last letter dated 11 January 1865, Hawkins

lamented that, despite his best  efforts,

he felt powerless to help his fellow prisoners. Although he died only a few

months later in November 1865 at the young age of 28, Hawkins

room-mate at Camp Chase remembered that “his abilities to minister, teach,

and govern the men while they were imprisoned helped their lives to become

enriched.”2

efforts,

he felt powerless to help his fellow prisoners. Although he died only a few

months later in November 1865 at the young age of 28, Hawkins

room-mate at Camp Chase remembered that “his abilities to minister, teach,

and govern the men while they were imprisoned helped their lives to become

enriched.”2

According to several sources, at least two of Hawkins’ poems were published after the war, “The Letter That Came Too Late” and “The Bonnie White Flag.” The latter was set to music and became popular with the soldiers of Camp Chase. In addition to these known poems, The Filson’s Tucker collection contains three original and unpublished poems by Hawkins as well as six letters to Lucy Tucker that help put his poetry in context. Together, these recently cataloged items document Hawkins’ short but spirited life and particularly his experience as a prisoner of war. Although he witnessed the downfall of his beloved Confederacy just months before his death, Hawkins penned these last prophetic lines in a poem entitled “The Captive’s Letter:”

“From the Harvest lands rise the

sweet song of the Reaper, / And the woodman’s axe rings in the forests

afar. / The tears shall be dry on the face of the weeper, / and flowers shall smile

from the furrows of war!”

“From the Harvest lands rise the

sweet song of the Reaper, / And the woodman’s axe rings in the forests

afar. / The tears shall be dry on the face of the weeper, / and flowers shall smile

from the furrows of war!”

1 Background information on Hawkins obtained

from Paul Clay’s, “The Men and Women of Camp Chase,” Hilltop Historical Society,

Columbus, Ohio.

1 Background information on Hawkins obtained

from Paul Clay’s, “The Men and Women of Camp Chase,” Hilltop Historical Society,

Columbus, Ohio.

2 Ibid.

The Filson Historical Society

1310 South Third Street - Louisville, KY 40208

Phone: (502) 635-5083 Fax: (502) 635-5086

Hours

The Ferguson Mansion and Office

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday and Sunday closed

Library

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday: 9 am. - 12 noon