Breaux Visiting Fellowships: Dr. Craig Friend returns to The Filson

By Dr. Craig T. Friend

Assistant Professor of History

University of Central Florida

Of all the territories of the trans-Appalachian west, there was none that inspired the American imagination

more than Kentucky. A lot of that inspiration arose from Kentucky’s situation at the confluence of

two historical themes that would dominate the nineteenth

century─the new West and old South. The new

West was defined by an unregulated and unquenchable quest for land that drove white Americans into all

reaches of trans-Appalachia.

Of all the territories of the trans-Appalachian west, there was none that inspired the American imagination

more than Kentucky. A lot of that inspiration arose from Kentucky’s situation at the confluence of

two historical themes that would dominate the nineteenth

century─the new West and old South. The new

West was defined by an unregulated and unquenchable quest for land that drove white Americans into all

reaches of trans-Appalachia.

As the first territory into which large waves of white settlers flowed, Kentucky was particularly susceptible to the problems of land hunger. Simultaneously, over the same years, southerners began to distinguish themselves and their region as different from northerners and the North, constructing a regional identity from the leisure, wealth, opportunities, and aspirations made possible by slave labor. Kentucky, as a slave state with moderate need for slave labor, was particularly susceptible as well to problems that would arise from the extension of slavery. . . .

While the contest between the West and South manifested most prominently in the Missouri Crisis and escalated in intensity until the explosion of sentiments that precipitated war in 1860, it began in Kentucky. In the first of the trans-Appalachian frontiers, white settlers confronted their hunger for land and their lust for success built upon slave labor. The two were not incompatible, at least not yet.. . .

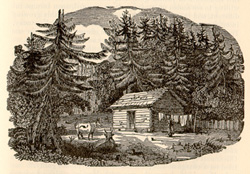

Rooted in our collective memory is the belief that Kentucky was a singular experience, the American frontier experience. Created by nineteenth-century historians determined to establish a colonial lineage for Kentucky, made sacrosanct by Frederick Jackson Turner and embraced by nineteenth- and twentieth-century popular culture, the notion that Kentucky’s frontier was uniformly a struggle of Indians against whites and their black slaves, and that this model of racial and cultural conflict repeated itself on each successive frontier as Americans continued westward, permeates American history and popular culture. The white men who encroached upon and settled Kentucky became cultural heroes, imbued with greater character than most actually had. The pioneer hero─as mythologized in John Filson’s 1784 portrait of Daniel Boone, in the ideal of the “Hunters from Kentucky’’ that was memorialized in song following the War of 1812, in the poetry of Lord Byron, in the character of Natty Bumppo who hunted and fought his way through James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales, in the 1939 movie Drums Along the Mohawk, in coonskin caps of the 1960s that identified viewers of Walt Disney’s Daniel Boone─was a Kentucky prototype of the frontiersman, of the genuine hero who, as historian Robert V. Remini put it, “took fantastic personal risks to realize a dream, a dream that ultimately benefited millions of others.”

As heroic as we have come to

understand Kentucky as West, there is another theme at work here.

Kentucky as South was not heroic; it was romantic and ultimately tragic.

“The sun shines bright on my old Kentucky home,” penned Stephen

Collins Foster in 1853, “’Tis summer, the darkies are gay; The corn top’s ripe

and the meadow’s in the bloom, While the birds make music all the day.”

With its suggestions of sunlight and harvest and melodic meadowlarks, the

song evoked nostalgia for the bucolic bosom of the South. But there, in the

first stanza, are also slaves─unignorable, unforgettable, essential

participants in the sowing and reaping. And later verses portrayed the institution

mores darkly, more harshly. Haunting in their portrayal of the

physical demands and psychological degradation of slavery,

Foster's lyrics evinced the dark side of Kentucky and the

South

As heroic as we have come to

understand Kentucky as West, there is another theme at work here.

Kentucky as South was not heroic; it was romantic and ultimately tragic.

“The sun shines bright on my old Kentucky home,” penned Stephen

Collins Foster in 1853, “’Tis summer, the darkies are gay; The corn top’s ripe

and the meadow’s in the bloom, While the birds make music all the day.”

With its suggestions of sunlight and harvest and melodic meadowlarks, the

song evoked nostalgia for the bucolic bosom of the South. But there, in the

first stanza, are also slaves─unignorable, unforgettable, essential

participants in the sowing and reaping. And later verses portrayed the institution

mores darkly, more harshly. Haunting in their portrayal of the

physical demands and psychological degradation of slavery,

Foster's lyrics evinced the dark side of Kentucky and the

South

. . . Tobacco, cotton, hemp─slave-produced staple crops had their chance in the Kentucky soils. Daniel Drake, who migrated as a boy in 1789, revisited his frontier home as an adult to discover that the log cabins were gone, replaced by fields of hemp. “The loss of the white population . . . has occurred in various parts of Kentucky, and must be referred to the influence of slavery,” Drake remarked. The imagery of the trials of Kentucky slavery and the harsh Kentucky overseer became particularly significant when, in 1852, Harriet Beecher Stowe published Uncle Tom’s Cabin, drawn largely from her own observations on visits to northern Kentucky. Their failure to quench the land hunger motivated men like the fictional Simon Legree to abuse others already less fortunate, emphasizing to a nation of readers the inherent contradictions between West and South that had emerged by the 1850s.

. . . Popular culture has

reinforced this image of Kentucky as South. Since the 1950s,

a white-clad southern gentleman has pawned Kentucky Fried Chicken, first

to a nation and then to the world. Every May, the sports world turns its

eyes to Louisville’s Churchill Downs where modern-day belles don

large-brim hats and beaux drink mint juleps as the horses run the Kentucky

Derby. Tony Horowitz’s 1998 Confederates in the Attic portrayed many

Kentuckians’ lingering southern loyalties as some of the most adamantly

racist in the region. And at the state’s flagship university, alongside the Star-Spangled Banner, football fans stand and sing one song to their old

Kentucky home so far away. In the mid nineteenth century, that matrix of

gentility, grace, racism, and nostalgia gave rise to pro-slavery rhetoric and

ultimately to the Civil War. Today, it continues to shape a sense of southern

regionalism that nurtures modern-day concepts of states’ rights, scriptural

definitions of morality, desires for a simpler rural way of life, and the

highest rate in the nation of persons returning to their home counties after

college graduation. So it is that two historical themes─the old South and the new West─defined and continue to define Kentucky.

. . . Popular culture has

reinforced this image of Kentucky as South. Since the 1950s,

a white-clad southern gentleman has pawned Kentucky Fried Chicken, first

to a nation and then to the world. Every May, the sports world turns its

eyes to Louisville’s Churchill Downs where modern-day belles don

large-brim hats and beaux drink mint juleps as the horses run the Kentucky

Derby. Tony Horowitz’s 1998 Confederates in the Attic portrayed many

Kentuckians’ lingering southern loyalties as some of the most adamantly

racist in the region. And at the state’s flagship university, alongside the Star-Spangled Banner, football fans stand and sing one song to their old

Kentucky home so far away. In the mid nineteenth century, that matrix of

gentility, grace, racism, and nostalgia gave rise to pro-slavery rhetoric and

ultimately to the Civil War. Today, it continues to shape a sense of southern

regionalism that nurtures modern-day concepts of states’ rights, scriptural

definitions of morality, desires for a simpler rural way of life, and the

highest rate in the nation of persons returning to their home counties after

college graduation. So it is that two historical themes─the old South and the new West─defined and continue to define Kentucky.

About |

The Filson Historical Society

1310 South Third Street - Louisville, KY

40208

Phone: (502) 635-5083 Fax: (502) 635-5086

Hours

The Ferguson Mansion and Office

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday and Sunday closed

Library

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday: 9 am. - 12 noon