The 1890 Louisville Cyclone

On March 27, 1890, Louisville was hit by one of the most violent and damaging storms recorded in its history. The 1890 cyclone became national as well as international news. Telegraphs came from all over the world offering to help with whatever aid was needed.

By Nettie Hance Oliver

Reference/Genealogy Specialist

About |

On March 27, 1890, Louisville was hit by one of the most violent and damaging storms recorded in its

history. Because of its widely spread, destructive path, which was much larger than the city had ever experienced,

it was referred to by residents and journalists as the “Louisville Cyclone.”

On March 27, 1890, Louisville was hit by one of the most violent and damaging storms recorded in its

history. Because of its widely spread, destructive path, which was much larger than the city had ever experienced,

it was referred to by residents and journalists as the “Louisville Cyclone.”

The early accounts tell us that telegraph dispatches came from Washington, D.C., on the afternoon of the 27th, warning of possible violent atmospheric conditions within the next few hours. All through the day the barometer steadily sank lower. How much advanced notice people received is unknown, but it is likely that news did not reach them in enough time to take proper shelter.

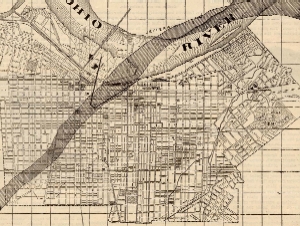

The storm hit at 8:30 p.m. and lasted only about five minutes, long enough to sweep over the downtown

area. The storm entered the southwestern city limits and tore across the West End in a southeasterly direction,

leaving behind a path of destruction.

The storm hit at 8:30 p.m. and lasted only about five minutes, long enough to sweep over the downtown

area. The storm entered the southwestern city limits and tore across the West End in a southeasterly direction,

leaving behind a path of destruction.

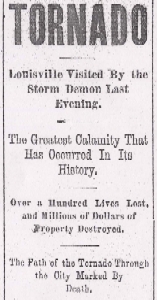

The storm destroyed dozens of residences, businesses, large stone warehouses, the railroad station and several churches. Ultimately over 100 lives were lost, and many more people were seriously injured. So localized was the path of the storm that thousands of Louisvillians went to bed that night totally unaware that disaster had struck the city. They were informed the next morning by The Courier-Journal headlines, “Louisville visited by the storm demon.”

One of the most tragic sites of the storm’s wrath was the Falls City Hall on West Market Street where a local

chapter of the Knights and Ladies of Honor were meeting when the storm hit. Located in the same building

on the lower floor were 50-75 children and their mothers, who were taking dancing lessons from Miss Annie App. The building

collapsed, burying about 200 people, many of whom perished. A first-hand account of a survivor at the Falls City Hall said that

the first sign of danger was the rocking of the building. Shortly after, a dormer window in the lodge room was blown from its casings,

and immediately plaster began to drop from the ceiling. Suddenly the floors gave way, and

all fell to the

basement level. Many who died suffocated in the wreckage or experienced fatal injuries from the fallen structure.

In less than five minutes of

One of the most tragic sites of the storm’s wrath was the Falls City Hall on West Market Street where a local

chapter of the Knights and Ladies of Honor were meeting when the storm hit. Located in the same building

on the lower floor were 50-75 children and their mothers, who were taking dancing lessons from Miss Annie App. The building

collapsed, burying about 200 people, many of whom perished. A first-hand account of a survivor at the Falls City Hall said that

the first sign of danger was the rocking of the building. Shortly after, a dormer window in the lodge room was blown from its casings,

and immediately plaster began to drop from the ceiling. Suddenly the floors gave way, and

all fell to the

basement level. Many who died suffocated in the wreckage or experienced fatal injuries from the fallen structure.

In less than five minutes of being hit by the tornado, the hall became nothing but a mass of shapeless brick and

mortar, a burial site of helpless victims. Thousands worked through the long and terrible night, retrieving the dead

and administering to the injured. The next day The Courier-Journal reported “A Story of Woe.” The most vivid

imagination could not adequately depict the scene of horror at the Falls City Hall.

being hit by the tornado, the hall became nothing but a mass of shapeless brick and

mortar, a burial site of helpless victims. Thousands worked through the long and terrible night, retrieving the dead

and administering to the injured. The next day The Courier-Journal reported “A Story of Woe.” The most vivid

imagination could not adequately depict the scene of horror at the Falls City Hall.

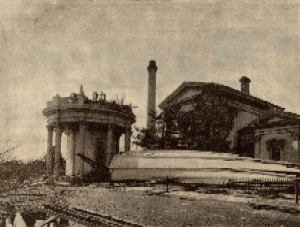

One of the great concerns was the destruction of the Waterworks stand tower, which could have resulted in cutting off the water supply to the whole city. The standpipe through which all water was forced into the reservoir was demolished; there was only enough water available to last six days. Louisvillians feared a water famine. Special notices appeared in the newspapers for water consumers to limit their use of water for only cooking and drinking.

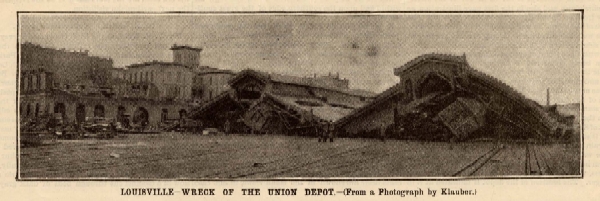

The Union depot railroad station on Seventh Street completely collapsed. Some heard the large building crack. The wind struck from the south and lifted the roof from the structure, throwing it several feet north. It was estimated that some 50 people were in the station when the cyclone struck. Many were trapped and seriously injured, but fortunately no one died.

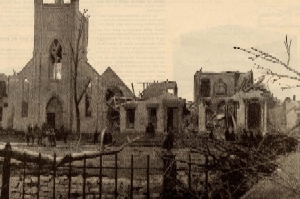

For the next few days, undertakers, priests and preachers were barely able to attend to the many calls for

their services. Undertakers from Indianapolis were called to aid the city. The streets were filled with

long funeral processions leading to the cemeteries in an almost constant stream. A shortage of hearses  resulted in two electric cars being chartered and used for a funeral cortege.

It was reported that five hearses stood in line at the Cathedral awaiting their turn for services. There was so much to

be done that funeral processions went to the graveyards in a trot and hearses

returned for another load as fast as could be driven. An especially sad scene was the funeral held at St. Paul’s

Episcopal Church on Jefferson Street for Reverend S.E. Barnwell, pastor of St. John’s, and his four-year-old son,

Dudley. Barnwell and his young son were in the rectory of the church when the storm hit. Mrs. Barnwell and three

other children were able to escape.

resulted in two electric cars being chartered and used for a funeral cortege.

It was reported that five hearses stood in line at the Cathedral awaiting their turn for services. There was so much to

be done that funeral processions went to the graveyards in a trot and hearses

returned for another load as fast as could be driven. An especially sad scene was the funeral held at St. Paul’s

Episcopal Church on Jefferson Street for Reverend S.E. Barnwell, pastor of St. John’s, and his four-year-old son,

Dudley. Barnwell and his young son were in the rectory of the church when the storm hit. Mrs. Barnwell and three

other children were able to escape.

The newspapers were full of notices for relief efforts and aid for the cyclone sufferers. The cyclone became national

as well as international news. Telegraphs came from all over the world offering to help with whatever aid was needed. Frank Leslie’s and Harper

Illustrated sent artists to the area for sketches for their papers. Miss Clara Barton, then president of the American

Red Cross, was summoned to Louisville to extend relief to the stricken citizens.

The newspapers were full of notices for relief efforts and aid for the cyclone sufferers. The cyclone became national

as well as international news. Telegraphs came from all over the world offering to help with whatever aid was needed. Frank Leslie’s and Harper

Illustrated sent artists to the area for sketches for their papers. Miss Clara Barton, then president of the American

Red Cross, was summoned to Louisville to extend relief to the stricken citizens.

Charles D. Jacob, mayor of Louisville, and General Taylor, the city’s chief of the police, ordered the Louisville Legion to patrol the affected

streets, to watch for thieves and looters, and to control the crowds of curious onlookers who had converged

onto the city to see the devastation. The Courier-Journal reported on March 28, 1890, “Thieves this morning,

hearing of the cyclone, came down the river in boats to rob the ruins of the Union depot, which was full of valuable

luggage and money. The thieves were warned that they would be shot on site, and not arrested.”

Charles D. Jacob, mayor of Louisville, and General Taylor, the city’s chief of the police, ordered the Louisville Legion to patrol the affected

streets, to watch for thieves and looters, and to control the crowds of curious onlookers who had converged

onto the city to see the devastation. The Courier-Journal reported on March 28, 1890, “Thieves this morning,

hearing of the cyclone, came down the river in boats to rob the ruins of the Union depot, which was full of valuable

luggage and money. The thieves were warned that they would be shot on site, and not arrested.”

Many local businesses ran ads in the local newspapers advising people of their business still in operation, and others

capitalized on the events by promoting their services. The German Insurance Company published a pamphlet, “That Awful Cyclone,”

that depicted scenes of the destruction to promote their insurance. Proprietors of lumber suppliers promoted sales on building

materials, advertising them in The Critic as tornado prices. One restaurant ad appeared saying, “Accidents will happen and sorrows lay their

burden at every door, but no matter what occurs, people must satisfy their appetite to sustain life. Our model restaurant was fortunate enough to

escape the cyclone’s wrath. Please come in today.”

Many local businesses ran ads in the local newspapers advising people of their business still in operation, and others

capitalized on the events by promoting their services. The German Insurance Company published a pamphlet, “That Awful Cyclone,”

that depicted scenes of the destruction to promote their insurance. Proprietors of lumber suppliers promoted sales on building

materials, advertising them in The Critic as tornado prices. One restaurant ad appeared saying, “Accidents will happen and sorrows lay their

burden at every door, but no matter what occurs, people must satisfy their appetite to sustain life. Our model restaurant was fortunate enough to

escape the cyclone’s wrath. Please come in today.”

Nothing could have prevented this storm from coming. If the current communication technology and weather-forecast

equipment had been available in 1890, the coming of the storm would have probably been reported in ample time to warn the people to

take shelter, and fewer people would have perished. The storm’s path went through the business area of the city

between 8-9 p.m., at which time the wholesale houses and the streets in the vicinity were comparatively deserted,

probably saving many lives. Had the storm struck in the daytime, hundreds would have been in the path of the

cyclone and would have likely lost their lives.

Nothing could have prevented this storm from coming. If the current communication technology and weather-forecast

equipment had been available in 1890, the coming of the storm would have probably been reported in ample time to warn the people to

take shelter, and fewer people would have perished. The storm’s path went through the business area of the city

between 8-9 p.m., at which time the wholesale houses and the streets in the vicinity were comparatively deserted,

probably saving many lives. Had the storm struck in the daytime, hundreds would have been in the path of the

cyclone and would have likely lost their lives.

The Filson Historical Society

1310 South Third Street - Louisville, KY 40208

Phone: (502) 635-5083 Fax: (502) 635-5086

Hours

The Ferguson Mansion and Office

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday and Sunday closed

Library

Monday - Friday: 9 am. - 5 pm.

Saturday: 9 am. - 12 noon